Ghostwriting traditionally involves a human collaborator who shares copyright with the credited author. But what happens when that “ghost” is an AI? U.S. copyright law grapples with the concept of authorship, and current guidance draws a firm line: only humans can be “authors” in the eyes of the law. This post explores the implications of collaborating with AI as a ghostwriter—examining U.S. Copyright Office (sometimes “USCO”) guidance, key developments like Zarya of the Dawn, and the unsettled gray areas where human creativity meets machine output.

Of great interest (maybe only to me) is that the “COMPENDIUM OF U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE PRACTICES” is in its third edition — released and effective December 22, 2014 and last modified January 28, 2021. That means more than four years have passed since it was updated. AI tech time runs even faster than internet company time. Unpacking that, it is an observation that the rate of change in the underlying technology for AI is very fast.

In January, 2021, OpenAI had just announced their DALL-E image generation technology. Generative text AI was starting to come into its own with GPT-3’s 175 billion parameter model. OpenAI hasn’t released numbers or their latest model, but today competitor Grok has 1.7 trillion parameters and estimates by third parties put OpenAI’s current model at a minimum of several trillion parameters. In the four years since the last US Copyright Office Compendium update, there has been incredible improvement to generative AI’s ability to kick out human-like works.

The US Copyright Office released a 3 part report analyzing copyright law and policy issues. A critical finding in the January 2025 “Part 2: Copyrightability” portion of the report found that “Based on the functioning of current generally available technology, prompts do not alone provide sufficient control” to make a work created by prompts copyrightable. We’ll explore that more below.

Human Authorship: The Primary Rule

The U.S. Copyright Office has made its stance clear: human creativity is required for copyright protection. The USCO position is that works entirely generated by AI (with no human input) are not copyrightable. As noted above, critically the Office found that merely providing prompts to an AI isn’t enough to create a protectable work — typing detailed instructions into a model does not by itself make the human a joint author. If a work contains more than a de minimis amount of AI-generated content, the applicant must disclose it and identify the human contributions. In essence, the law views AI outputs as akin to uncopyrightable material (like facts or mechanical processes) unless a human’s creativity meaningfully shapes the final work.

This principle was underscored in Thaler v. Perlmutter, where a researcher sought to register a copyright for an image generated by an AI system. In 2023, a federal court upheld the Copyright Office’s denial, ruling that a work created “absent any guiding human hand” cannot be copyrighted. The court affirmed that an AI, not being human, cannot be an author under U.S. law, echoing a longstanding rule that copyright protects only creations of human intellect. This outcome aligns with earlier precedents (for example, the “monkey selfie” case, Naruto v. Slater, where a photograph taken by a monkey was deemed unprotectable for lack of human authorship). The bottom line: regardless of how impressive or creative an AI’s output seems, without human creative input it lies outside copyright’s umbrella.

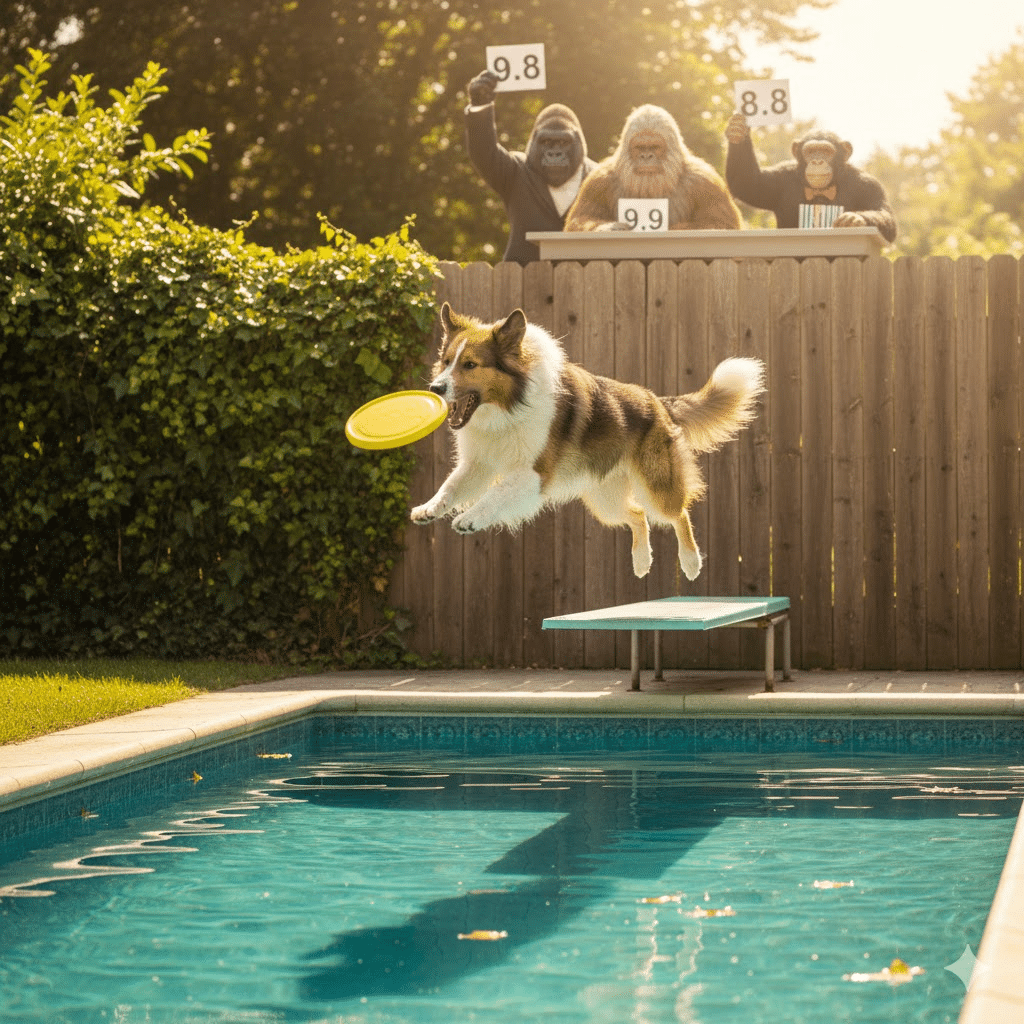

Gary’s Dog: Iterative Prompting

There is little question that a complex prompt itself can be copyrighted. The phrase “please create an image of a cute dog that is 1/4 collie and 3/4 german shepherd and is jumping off the diving board of a swimming pool, trying to catch a frisbee in her mouth; the pool is relatively narrow at the point where the diving board is located.; behind the diving board is a wooden fence with about 1 meter of ivy planting in front of it; it is a nice sunny day, and the color temperature should reflect that; in the background are three judges, a gorilla, a bigfoot, and a chimp holding up signs rating the dive (like at the olympics) with a score of 9.8, 9.9, and 8.8 respectively; there are a few scattered leaves floating in the pool; the frisbee is about 20 cm away from the dog’s mouth, and she is about to catch it” is copyrightable. The prompt has human creativity and is expressive enough to qualify. It follows that the image generated by that prompt would be a work of joint authorship, with portions generated by my prompt, and other portions filled in by the AI on its own. Let’s have a look at what Gemini 2.5 Pro does with that prompt:

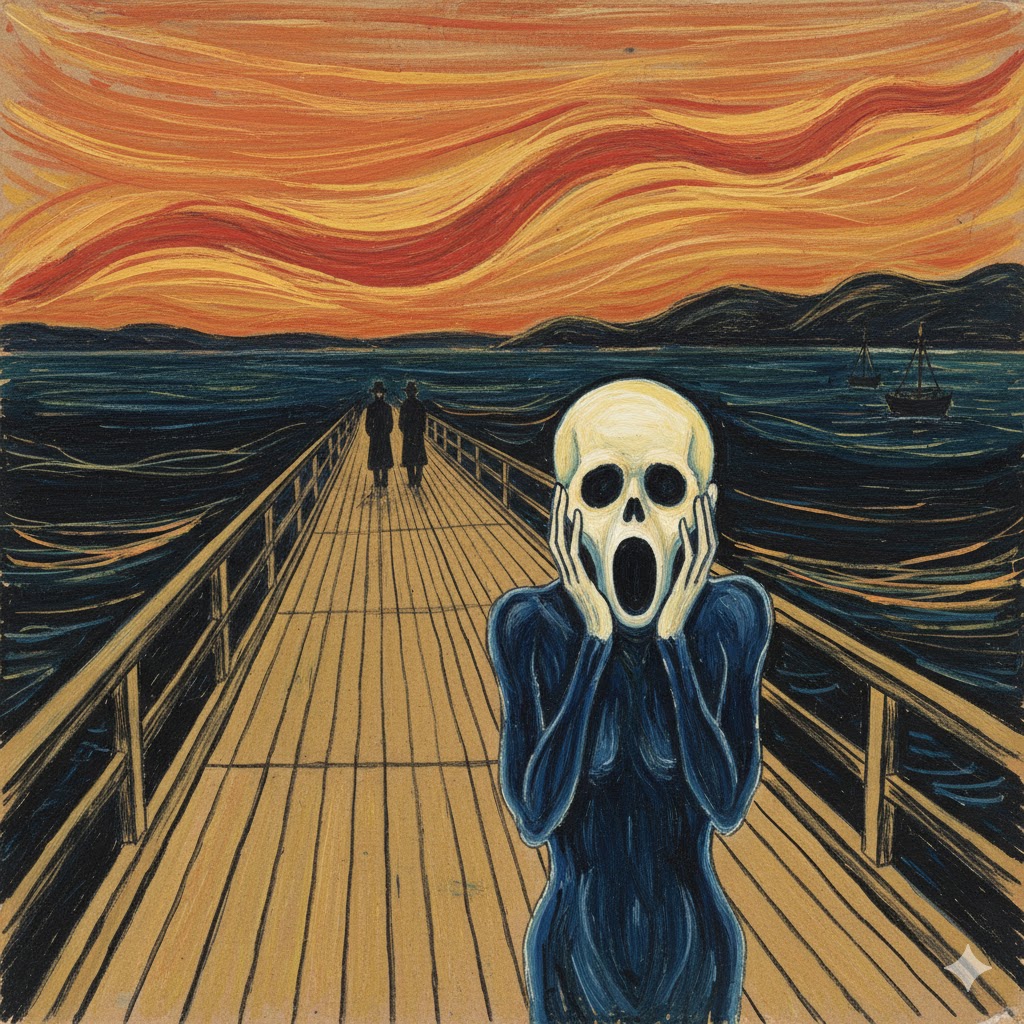

Let’s consider the copyright implications. The diving board, the dog and the frisbee came from my prompt. However, the grass in the background did not. It follows, then, that I hold a copyright in parts of the image but not others. You can see how this can quickly become nightmarishly complex. The Copyright Office’s guidance that prompts do not provide enough control to make the output reflect the human creativity is pretty clearly wrong in practice (as the bizarre image above shows). Let’s try something else probative: We’ll ask AI to describe “The Scream” and see if it can create the drawing. The prompt is ** really long ** and reproduced at the end of this post.

The image above is obviously (to my eye) a derivative work of “The Scream”, yet it was created solely using a prompt that does not mention the name of the painting at all. If the U.S. Copyright Office is correct that no copyright exists in AI output regardless of the prompt, it raises the question of whether an adequately described work could recreate a copyrighted image without infringing. The answer should be an obvious “no”, but the guidance seems to hint that the answer is “yes”.

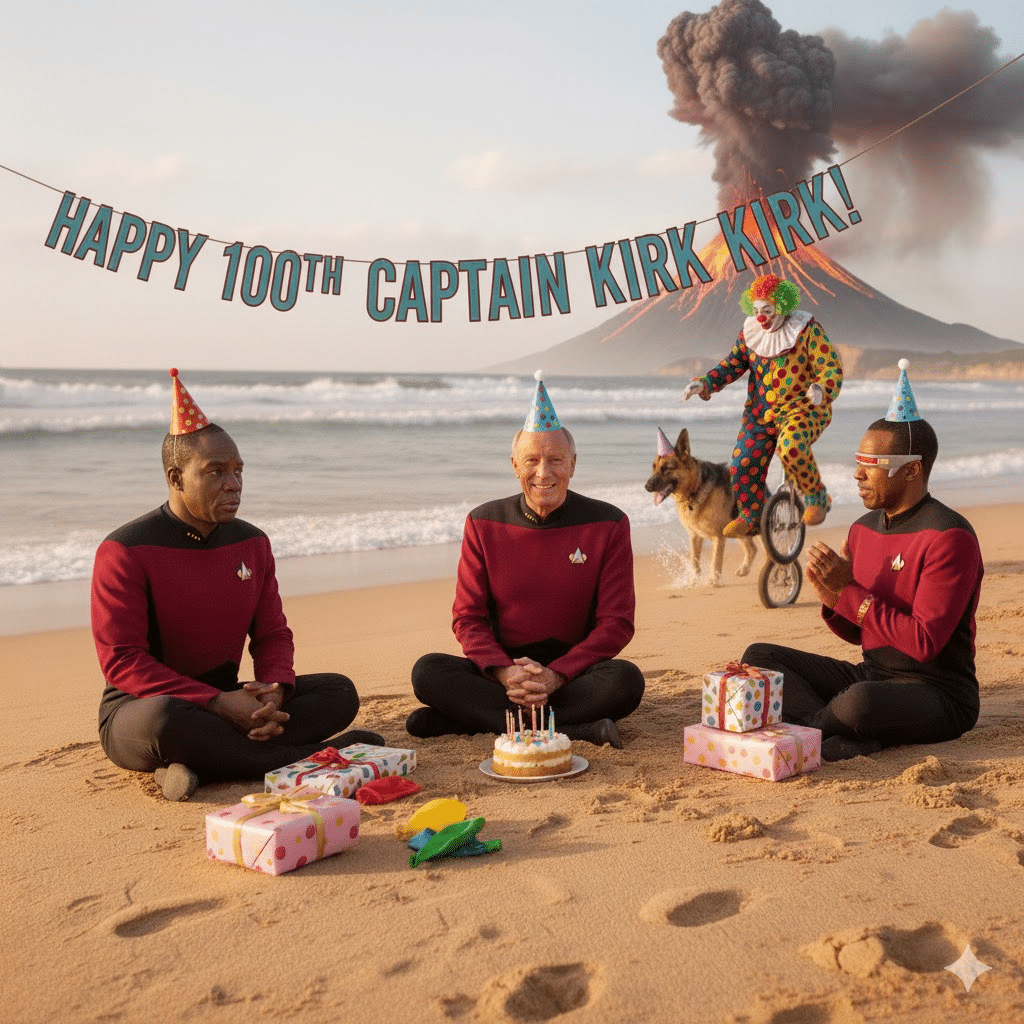

Now let’s start with a prompt that probably wouldn’t be copyrightable: “Make a dog”. Nice, image 1 is a golden retriever. Now let’s start iterating. I want the dog to be on the beach. “Please put the dog on the beach”. Kind of boring. Let’s have the dog wearing a birthday party hat: “Please have the dog wear a birthday party hat”. Nice, but not festive enough. “Please have other dogs at the party”. Let’s make it more interesting. “Add a volcano erupting in the distance.” Still not strange enough for me. “Please add a clown riding a unicycle in the background”. Perfect! My artwork is complete:

At some point between the first image — clearly not copyright — and the last, copyright (probably, but not according to USCO guidance that says no prompt is sufficient to guide an AI to reflect human creativity) arose. Rules addressing this situation in a realistic way have yet to be written in copyright offices and legislatures throughout the world, but it will almost necessarily involve a subjective assessment: At what point has the creative input via prompting resulted in a copyrightable work? § 102(a) of the U.S. Copyright Act separately lists “literary works” and “pictorial” works, but this is a hybrid. The human contribution was entirely textual. The artistic work was entirely machine-driven. It isn’t even clear what category this work falls under.

This seems like a new problem, but it has historical analogues. For example, the characters and universe of “Star Trek” are copyrighted. I can’t just write a script set in “The United Federation of Planets” and have Captain Picard lead a team of other known characters through adventures without infringing that copyright. It would be a derivative work, with copyright to the original portions of the Star Trek universe held by that copyright owner, and the original elements held by me. Is it the same in the case of my “Dog Birthday Party With Unicycle Clown, Party Hats, and Erupting Volcano” image? It should be, but it would be far better for legislatures to clarify the law than to have courts try to apply laws written for paintings to AI-assisted creations.

For educational purposes, let’s look at how the Star Trek example might play out as an image. I added “Now replace the dogs with Captain Picard, Worf, Commander Data and Commander LaForge, all celebrating Captain Kirk’s 100th birthday.”. It is pretty clear that Gemini has some guardrails, because it did not create the exact characters I asked for, but it still harkened back to Star Trek, and includes the copyrighted look and feel of the characters:

The actual rendering of the image was done with AI, so there is no copyright to the flourishes it created without prompting, like the footprints in the foreground. The characters are mine (the dog and the clown on the unicycle) and Star Trek’s. If we added in a version of Mickey Mouse that is still copyright, we’d have a triple derivative work. The complexity of the problem isn’t hard to see.

Zarya of the Dawn: A Live Example

A historical example of this mishegas in practice is the case of “Zarya of the Dawn.” In 2022, author Kristina Kashtanova used the AI tool Midjourney to generate artwork for a graphic novel and initially obtained a copyright registration. But the U.S. Copyright Office later revisited that registration, ultimately canceling it in part. The Office concluded that while Kashtanova could claim authorship over the text and the selection, coordination, and arrangement of elements in the novel, the AI-produced images did not meet the requirement of human authorship. The Office reissued a certificate covering only the portions of the work Kashtanova created without Midjourney’s help. In other words, the overall comic book could be partially protected (for its story and the human creative choices in how images and text were combined), but the individual AI-generated illustrations themselves were denied protection as original works.

“Zarya” highlights the nuanced outcomes when a human and AI “co-create.” The human’s contributions (writing the narrative, arranging panels, etc.) remain protected, but the AI’s contributions fall into the public domain. This raises practical questions: if an author uses AI for a draft or an image and then revises or incorporates it, how much revision is needed before the result is considered human-authored? The Copyright Office has indicated that minimal editing of AI output (like touch-ups or selection among options) may not suffice – the human must contribute their own creative expression. In Kashtanova’s case, their curation and story composition were protectable, but not the raw AI art. The situation creates a patchwork of rights: parts of a collaborative human–AI work might be copyrighted to the human author, while other parts (the AI-generated pieces) might be free for anyone to reuse.

Unsettled Areas and Future Outlook

The intersection of AI assistance and copyright law is full of unanswered questions. One grey area is threshold of creativity: how much human input into an AI’s output is needed before the human can be considered an “author”? Only where the human’s creative process truly shapes the expression (rather than the AI determining it autonomously) will the result likely qualify for copyright. For instance, using an image-generating AI and then painting over it or collaging multiple AI outputs might yield a human-authored work, whereas simply choosing the best AI-generated paragraph out of five options probably would not.

Another unsettled issue is joint authorship in collaborations involving AI. With two human co-authors, each owns a share of the copyright. But an AI cannot hold copyright, so if an AI “collaborates,” the human user might be deemed the sole author of whatever portions are sufficiently human-driven. Alternatively, the AI-produced portions might be viewed as uncopyrightable fragments inserted into a larger work. This complicates scenarios like an author using AI to ghostwrite portions of a novel or article. The human may claim full ownership only if they can show they creatively arranged or revised the AI content in a way that meets the originality standard. If not, the AI-written chapters could be unprotected text intermingled with the author’s protected chapters – a nightmare for determining rights. We’re essentially seeing a new species of derivative work questions: is an AI’s output a kind of raw material that an author can transform and claim, or an independent creation that no one can own?

Practical Guidance: Keep a copy of all prompts and AI outputs. This will allow a delta (or redline or blackline, basically a comparison between the AI output and the final product) to be generated, making the copyright office’s job of determining which parts of the output are human much easier. This could be the difference between winning and losing copyright infringement claims in court.

For now, the U.S. Copyright Office’s position is firm: no human authorship, no copyright. Even compex, creative prompts aren’t enough to create copyright in the output. Legislative or judicial developments could clarify matters down the road. Courts might eventually tackle scenarios like an AI-assisted screenplay or a machine-generated painting curated by a human, and refine the tests for authorship. Until then, creators using AI as a ghostwriter face a trade-off: they can leverage the technology’s prowess, but they must be prepared to do enough creative work themselves to secure copyright – or risk parts of their creation wandering unprotected in the public domain. In short, if your ghostwriter is a ghost in the machine, you may end up being the only legally-recognized author in the room (for better or worse).

Appendix A: Gemini Pro’s Detailed Instructions to Reproduce “The Scream”:

Part 1: Materials and Preparation 🎨

To best replicate the original’s texture and appearance, we will work with mixed media on a rigid surface.

Required Materials:

- Surface: One piece of unprimed cardboard, approximately 36 inches tall by 29 inches wide (91 cm×73.5 cm). The raw, slightly absorbent nature of the cardboard is essential to the final look. Do not use a gesso-primed canvas.

- Paints: You’ll need a limited palette of tempera paint or, if unavailable, gouache or very fluid acrylics. The colors are crucial:

- Cadmium Yellow Light

- Cadmium Orange

- Cadmium Red Deep (a blood-like red)

- Pthalo Blue (or Prussian Blue)

- Ultramarine Blue

- Burnt Sienna

- Ivory Black

- Titanium White (to be used sparingly)

- Drawing Tools: A set of wax crayons or oil pastels. You will need black, dark blue, a pale yellow-white, and orange.

- Brushes: A variety of flat and round brushes. You’ll need at least a 1-inch flat brush for the large areas and a smaller round brush for finer details. Don’t use pristine, perfect brushes; older, slightly worn brushes will help achieve the desired raw texture.

- Palette: A surface for mixing your colors.

- Water Container and Rags: For cleaning brushes.

Preparation:

- Place your cardboard on an easel or a flat surface where you can work comfortably. The orientation must be portrait (vertical).

- Arrange your paints and crayons so they are easily accessible.

- Internalize the core emotion: anxiety. Imagine a moment of intense panic where the world around you seems to warp and vibrate with your own inner terror. This is the feeling you will translate into color and line.

Part 2: The Foundational Composition

We’ll divide the canvas into three main visual zones: the Sky (top third), the Fjord and Landscape (middle third), and the Bridge and Figures (bottom third and extending upwards).

Initial Sketching (Use a light pencil or a very thin wash of light brown paint):

- The Horizon Line: This is not a straight line. Draw a wavy, undulating line that separates the sky from the fjord. It should start about one-third of the way up the canvas on the left side and curve gently downwards before rising again on the right side.

- The Bridge: This is the most important structural element. It will create a powerful sense of forced, aggressive perspective.

- Start at the very bottom-left corner of your cardboard. This is the closest point of the bridge to the viewer.

- Draw a strong, straight diagonal line from this corner, aiming for a point about halfway up the canvas on the right-hand edge. This is the left railing of the bridge.

- Draw a second diagonal line, parallel to the first. This line should start about one-fifth of the way in from the left at the bottom edge and run parallel to the first railing. This is the right railing.

- The space between these two lines forms the walkway of the bridge. Notice how it recedes into the distance at a sharp, unsettling angle.

- Placement of Figures:

- The Main Figure: This figure will be in the immediate foreground. Its head should be roughly centered horizontally on the canvas, but its vertical position is low, with the bottom of its form being cut off by the bottom edge of the cardboard. Make a simple oval for the head and a fluid, ghost-like shape for the body below it.

- The Background Figures: Far down the bridge, roughly two-thirds of the way to the vanishing point, sketch two simple, upright vertical shapes. They should appear small due to the distance. They will be walking away from the viewer.

Part 3: Painting the Sky and Fjord (The World of Turmoil)

This section is about creating a visual representation of a panic attack. The sky and water are not separate entities; they are a swirling vortex of color and emotion.

Step 1: The Fiery Sky

The sky is a blaze of unnatural, sickly color. Your brushstrokes must be long, fluid, and sinuous, like sound waves or raw energy.

- The Orange and Yellow Base: Begin with Cadmium Orange and Cadmium Yellow. On your palette, create a range of tones from a pure, vibrant orange to a pale, sickly yellow (mix yellow with a tiny amount of white).

- Application: Using your 1-inch flat brush, apply these colors in broad, undulating, horizontal bands across the top third of the canvas.

- Start with a deep band of Cadmium Orange at the very top. Let the brushstrokes be visible and streaky.

- Below this, sweep in a band of Cadmium Yellow.

- Don’t blend these colors perfectly. Let them touch and streak into one another, but maintain the feeling of distinct bands of color. The lines should not be perfectly straight; they should ripple and wave, as if the sky itself is vibrating.

- The Blood-Red Intrusion: Now, take your Cadmium Red Deep. This is the most aggressive color.

- Load your brush and, with a powerful, confident motion, sweep a thick, wavy river of this red through the orange and yellow bands. It should feel like an open wound in the sky. It should primarily move from the upper left, curving down towards the center.

- Add another, thinner streak of red elsewhere to create an echo. The effect should be jarring and violent.

Step 2: The Dark Fjord

The fjord is the abyss. It is a pool of darkness that reflects the terrifying sky.

- Mixing the Deep Blue-Black: On your palette, mix your Pthalo Blue or Prussian Blue with a significant amount of Ivory Black. You want a color that is almost black but has a deep, cold blue undertone.

- Application: Fill the area below the sky’s horizon line with this dark mixture. The brushstrokes should be just as expressive as the sky’s, but they should follow the contours of the landscape you sketched.

- Make the strokes swirl and curve, especially around the landmasses. The water should not feel calm; it should feel like a churning whirlpool of dread.

- Reflecting the Chaos: While the dark blue-black paint is still wet, take a small, clean brush and pick up some of the pure Cadmium Orange and Cadmium Yellow from your sky palette.

- Lightly streak these colors into the upper parts of the fjord. These are not clear reflections; they are distorted, sickly echoes of the sky’s horror, as if the water is contaminated by the sky’s emotion.

- Defining the Shoreline: Using your dark blue-black mixture with maybe a touch of Burnt Sienna, paint the distant shoreline. It should be a simple, dark, undulating form. On this shoreline, to the right, paint two very simple, almost abstract shapes of boats. They are just small, dark masses with a single vertical line for a mast.

Part 4: Painting the Bridge and Figures (The Human Element)

The bridge is a rigid, man-made structure that thrusts you into this chaotic world. It offers no escape.

Step 1: The Unstable Walkway

The perspective of the bridge must feel wrong, steep, and vertiginous.

- Color Palette: Mix Burnt Sienna, Cadmium Yellow, and a touch of black to create a dirty, mustard-like brown or ochre.

- Application: Using a flat brush, apply this color to the walkway. Your brushstrokes are critical here. They must be long, straight, and rigid, perfectly following the diagonal lines of the bridge you sketched earlier.

- This will create a powerful contrast with the swirling, organic lines of the sky and fjord. The bridge should feel like it’s racing away from you into the distance.

- Do not make the color flat. Allow some of the raw cardboard to show through in places. Use your black crayon or a thin brush with black paint to reinforce the lines of the planks and the railing, making them stark and aggressive.

Step 2: The Two Distant Figures

These figures represent the indifferent world, oblivious to the protagonist’s inner crisis.

- Painting Them: Use your dark blue-black mixture. Paint these two figures as simple, almost flat silhouettes.

- They are walking away. You can suggest a hat on one and a long coat. There is no detail. They are just dark, upright shapes against the chaotic background. Their posture is rigid and normal, which makes the main figure’s contortions even more striking.

Step 3: The Screaming Figure

This is the emotional core of the entire painting. Take your time here. The figure is not quite human; it is a raw embodiment of anguish.

- The Robe/Body: The body has no discernible form. It is a fluid, serpentine column.

- Using your dark Ultramarine Blue and Ivory Black, paint the figure’s robe. The brushstrokes should be flowing and curved, echoing the lines of the landscape behind it. The form should feel boneless and distorted, as if the figure’s very substance is being warped by its emotion. Let the strokes be loose and expressive.

- The Hands and Head: This is where you will use your crayons and finer brushes.

- Color: Mix Titanium White with a large amount of Cadmium Yellow Light and a tiny, tiny speck of Pthalo Blue or black. You want to create a pale, corpse-like, sickly flesh tone. It should look unhealthy and ghostly.

- The Head: Paint the head in this color. The shape is like an elongated skull, bald and androgynous. There are no ears and no hair. It is a primitive, primal shape.

- The Hands: Paint the two hands in the same sickly color. They are elongated and skeletal. They are not covering the ears, but rather pressed against the cheeks, framing the head as if to hold it together from imploding.

- The Features (Crucial Detail): Now, switch to your black crayon or a small brush with black paint.

- The Mouth: This is the focal point. Draw a perfect, dark, gaping oval. It is a void. It is a silent scream, a black hole of despair.

- The Eyes: These are not eyes. They are two dark, hollow sockets, similar in shape to the mouth but smaller. There are no eyeballs, no life in them—only emptiness.

- The Nostrils: Add two small, dark dots for nostrils.

Part 5: Final Touches and Review

Step back from your work. The final piece should feel dissonant and emotionally charged. The straight, rushing lines of the bridge should clash with the swirling chaos of the natural world. The ghostly, contorted main figure should stand in stark contrast to the rigid, oblivious figures in the background.

- Texture: Look for areas where you can enhance the texture. Use your crayons to add rough, linear details. Go over the railings of the bridge with the black crayon to make them feel sharp and coarse. You can even add some light, frenzied orange crayon strokes in the sky to heighten the sense of vibration.

- Emotional Read: Does it make you feel uneasy? Does the perspective make you feel a little dizzy? Do the colors feel “wrong”? If so, you have successfully captured the essence of the work. The painting is not finished when it looks “correct,” but when it feels correct.

Pingback: Copyright in Two Minutes.

Pingback: Generative AI and IP Law: Navigating the Uncertainty